Timely, targeted and short, ‘microtutorials’ are increasingly common for those of us who use smart devices. When you download an app, you will often be walked through how to use it. You are shown the key features.

You might practise using them (like how to ‘swipe’ to change screen)1. You receive ‘microdoses’ of teaching – tiny tutorials to build your awareness, capability and motivation to use the feature.

Low engagement with safety features (PDF, 698.2 KB) is a problem in online safety. We were interested in whether these new tools could help rapidly engage and educate users on the features available.

Boosts

The behaviour we targeted was reporting of potentially harmful content. Around six in ten (PDF, 698.2 KB) users report experiencing harmful online content or behaviour in the last four weeks. Reporting helps highlight this content to platforms.

Ofcom’s behavioural insight specialists previously ran an experiment (PDF, 1.8 MB) investigating the effect of prompts and nudges to encourage reporting. In contrast to those ‘in the moment’ nudges, microtutorials take a different approach – ‘boosting’ reporting by building users’ capabilities to report.

Our experiment is grounded in boost theory. Unlike nudges, which use choice architecture to guide a decision ‘in the moment’, boosts foster competence, mainly through skills, knowledge and decision tools2. The theory is that boosts have the potential for lasting effects beyond the moment of choice.

But boosts may not just build capability. The COM-B model, which we’ve discussed before, tells us that a change in capability can influence motivation to take action. Microtutorials aim to enrich users’ capabilities, but in principle can also influence motivation and ultimately behaviour.

What boosts a boost?

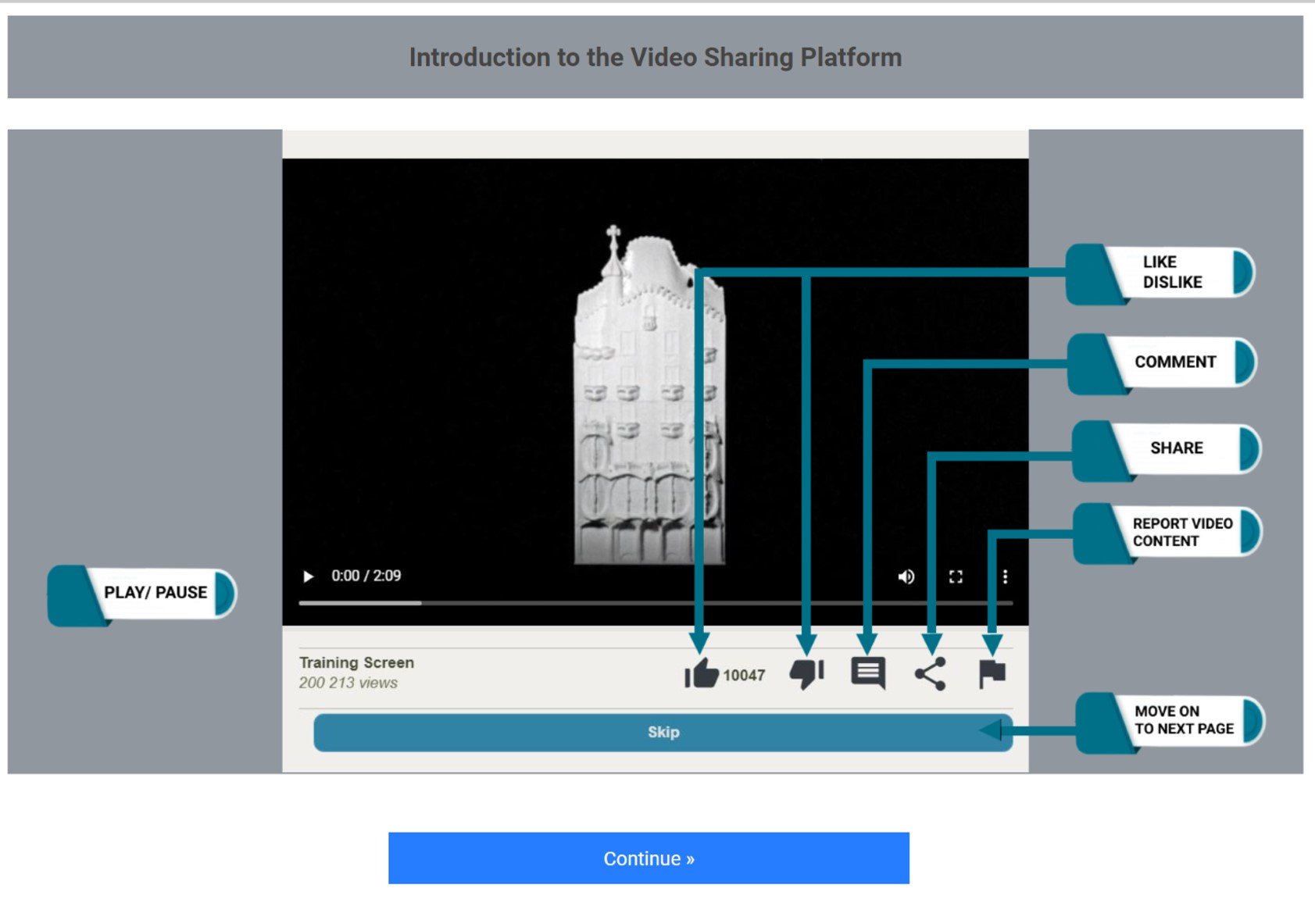

The static version aimed to test a microtutorial at its simplest. It is quick with no-frills.

The video microtutorial tests whether a more engaging user experience increases effectiveness. The prevalence of video-sharing platforms indicates the appeal of this format.

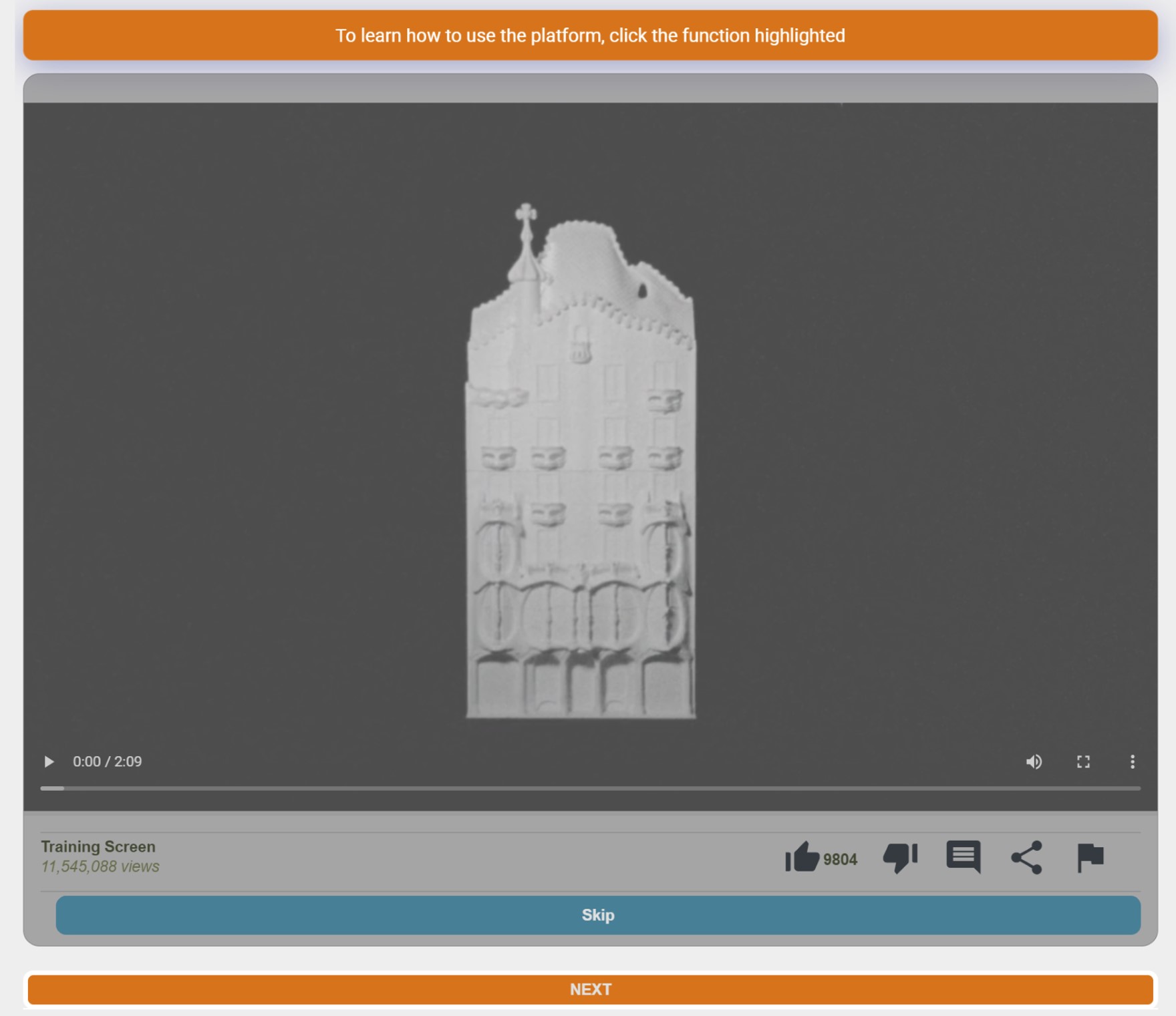

The interactive version builds on the insight from our serious game trial, which found that interactivity enhanced learning. It also builds on the growing body of educational research that suggests that active learning is more effective than passive learning3.

Our experiment

Participants were randomly allocated to take one of the microtutorials or no microtutorial (the ‘no information’ control group). They did not have the option to skip the microtutorial. They then watched six videos – three neutral, three containing potentially harmful content – in randomised order. Participants were given no specific task other than to browse the videos and interact with them as they normally would. There was no instruction to report or carry out any other activity. We wanted to see the effect of the microtutorial on general browsing behaviour.

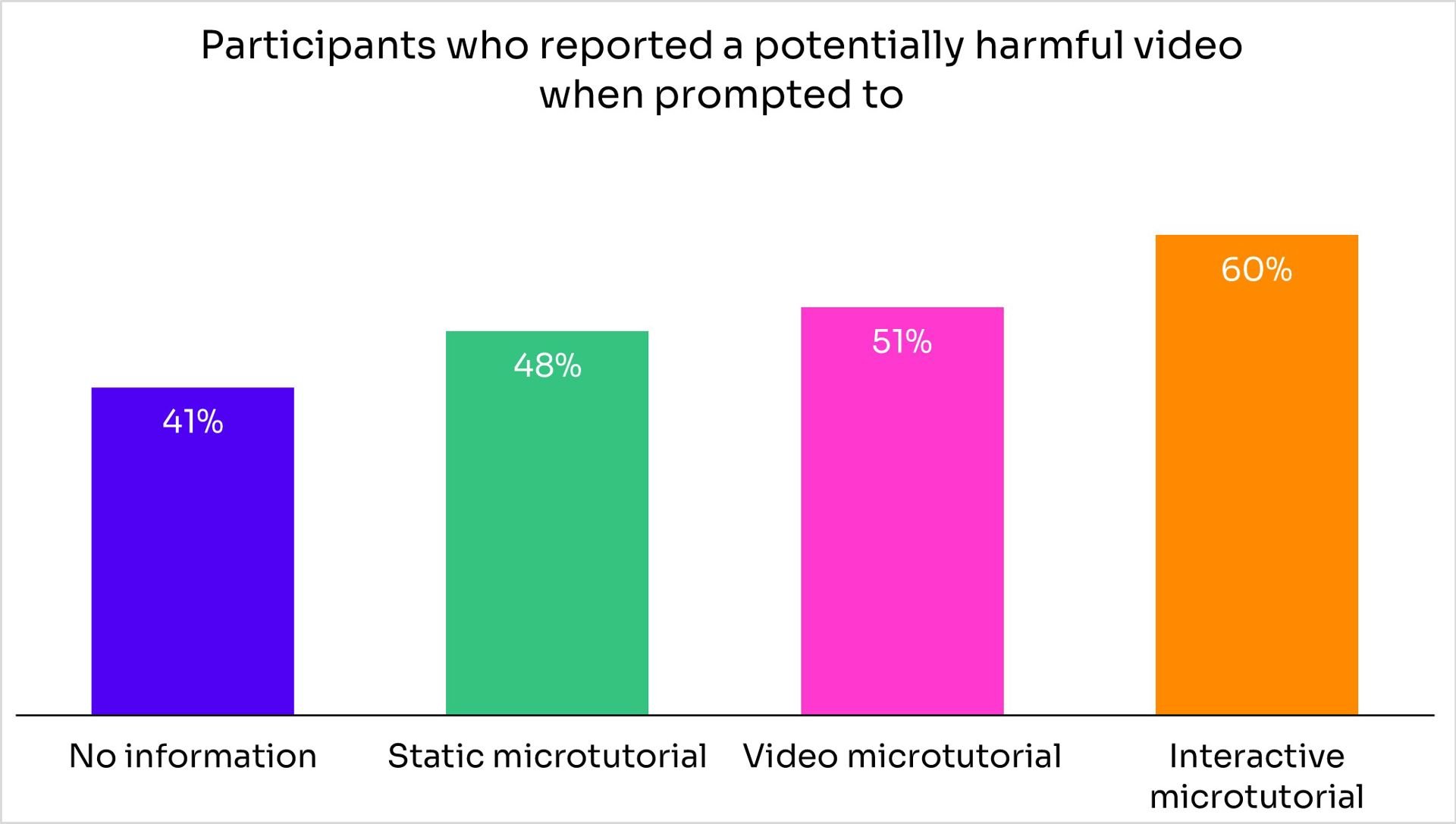

Additionally, we asked users expressly to complete a report on a further video. This section of the experiment explicitly tested the effect of the microtutorial on capability.

The experiment concluded with questions on participants’ views on VSPs, reporting and their specific microtutorial.

Five insights

- All the microtutorials significantly increased reporting when specifically prompted. Microtutorials can clearly play the limited role of boosting capability4.

- Turning to whether they can also build motivation, with no microtutorial, participants did not report much – only 4% reported at least one potentially harmful video. That means only 4% who saw a potentially harmful video were motivated to report it. Even the remarkably basic, static microtutorial has a significant impact – 9% reported at least one potentially harmful video5. Simply getting users to pause, pay attention and briefly interact with the information increased use of the safety feature.

- The video and interactive microtutorials were even more effective – 16% in the video group reported at least one potentially harmful video, 23% of the interactive group. These are large effects6. They suggest that microtutorials can boost behaviour – not just capability. The success of the interactive version compared to the video also tells us that, at least in our experimental setting, interactivity trumps user-experience in driving impact. Practising a behaviour, even just once, can enhance learning and motivation to enact that behaviour.

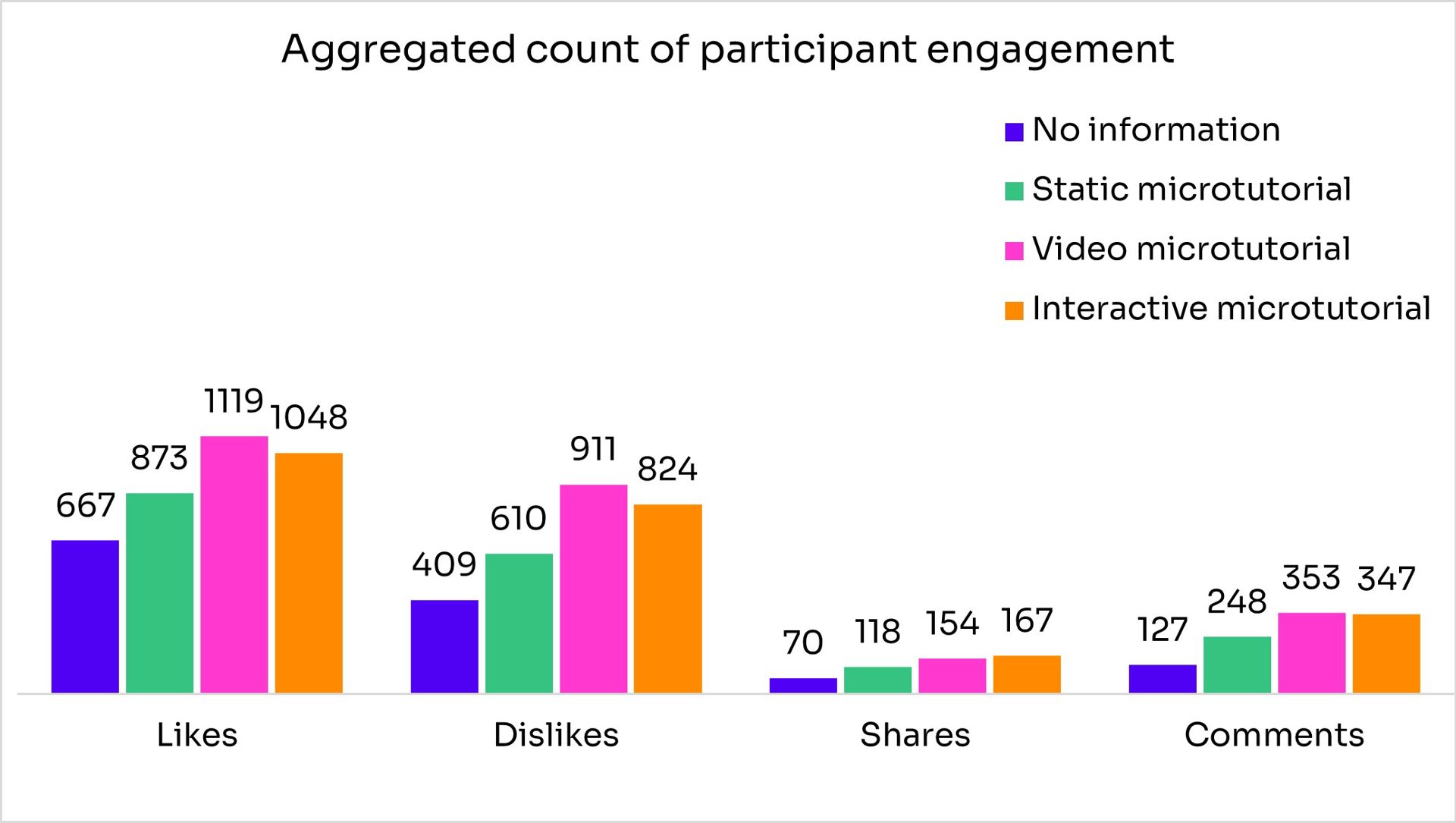

- Driving up reporting can risk increasing spurious reports which place a burden on platforms. However, the microtutorials did not increase reporting of neutral content relative to the ‘no information’ group.

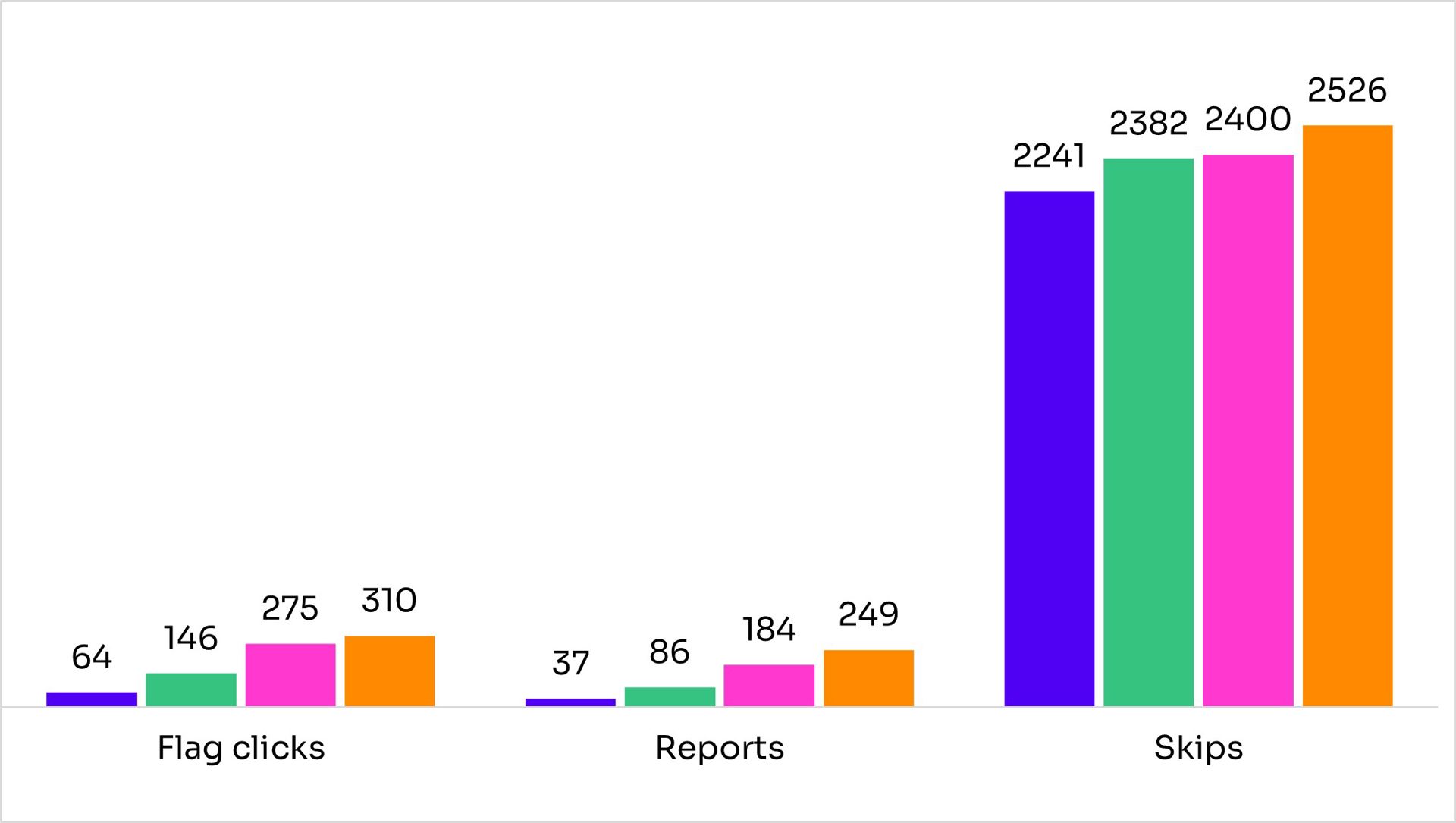

- The video and interactive microtutorials had positive spillover effects. Participants became more engaged with the platform all-round – they did more liking, disliking, commenting7, etc. And they told us that they gained greater confidence in using video sharing platforms more generally – not just the one they used in the experiment8.

In the real world

It is important to remember the limitations of this kind of study. Participants know they are in an experiment and may not act how they normally would. T his experiment cannot teach us about the ongoing impact of microtutorials. We cannot yet say whether they have the lasting effects that boost theory suggests.

Nevertheless, the experiment suggests that microtutorials can play a role in ‘activating’ users to engage with safety measures, and gives insights into what makes them work. It is striking that even very basic microtutorials have a significant effect, and that impact can be enhanced with interactivity.

There is further potential. The microtutorials we designed were not polished nor targeted at specific features. There is considerable scope to improve the user experience and reduce their duration. This could improve their effectiveness while also reducing the interruption to the user journey.

On the other hand, in contrast to most real-world examples, our participants did not have the option of skipping the microtutorial. This allowed us to learn about their relative effectiveness but does mean we do not know how many users would engage with the microtutorial if they were optional. We’re interested to find out.

Help us learn more

Developing evidence on the promise offered by microtutorials has helped us build knowledge on the range of online tools available to encourage safety behaviours. We want to generate more evidence on the impact of ‘boost’ interventions. Get in touch about related research or if you would like to explore a trial with us.

For further detail on the design and interpretation of these results, read our discussion paper. Our technical paper (PDF, 1.5 MB) details the statistical analysis of the data.

Amy Hume wrote this piece, based on research by Rupert Gill, Amy Hume, John Ivory and Pinelopi Skotida with Kantar Public Behavioural Practice.

Disclaimer: The analyses, opinions and findings in this article should not be interpreted as an official position of Ofcom. Ofcom’s Behavioural Insight blogs are written as points of interest and are the personal views of the author(s). They are not intended to be an official statement of Ofcom's policy or thinking.

[1] Source: A Beginners Guide to Setting Up the Google Pixel 6 Pro, YouTube, uploaded by Tech With Brett, 29 January 2022.

[2] For a considered guide, see Elina Halonen’s Nudge, boost, budge and shove - what do they all mean? (squarepeginsight.com)

[3] In experimental settings, there’s a risk of social desirability bias – participants might report more because they pick up a sense that that’s what the trial is looking at. To avoid this, the microtutorials taught all the features of the platform (play, pause, like, dislike, comment, share, report, skip) so that no specific feature was seen to be encouraged.

[4] Static microtutorial statistically significant at 5% level (p<0.05), video microtutorial and interactive microtutorial statistically significant at 0.1% level (p<0.001)

[5] Statistically significant at 1% level (p<0.01)

[6] Video microtutorial and interactive microtutorial statistically significant at 0.1% level (p<0.001)

[7] Additional analysis is still to be conducted on these measures

[8] Video microtutorial and interactive microtutorial statistically significant at 0.1% level (p<0.001)