Autoplay and autoskip could be used to undermine – or enhance – online safety measures.

Messages that alert users to potentially harmful content can play a significant role. We found that, after viewing one of these warnings, up to 51% of participants chose to avoid potentially harmful content.

But there is evidence that the wider browsing environment shapes user behaviour, and not always positively. Features such as autoplay (where the next video begins to play without users initiating it) and infinite scrolling may promote addictive online behaviours or reduce users’ sense of control. This raises the possibility that they could influence the effectiveness of safety features such as alerts.

But there is evidence that the wider browsing environment shapes user behaviour, and not always positively. Features such as autoplay (where the next video begins to play without users initiating it) and infinite scrolling may promote addictive online behaviours or reduce users’ sense of control. This raises the possibility that they could influence the effectiveness of safety features such as alerts.

In our latest trial we focused on autoplay. On Facebook or Twitter/X, clips play automatically when you scroll. On YouTube, a new video plays automatically after eight seconds.

We know that alerts can be effective when they require users to stop and make a choice. But is that effect undermined when combined with autoplay? If it is, that raises the risk that autoplay could be used to engage users with potentially harmful content rather than help them make informed choices about viewing it.

But it’s important to remember that most online choice architecture can be used to help as well as hinder users. In addition to testing whether autoplay could reduce the effectiveness of alerts, we also tested whether autoskip – making it the default for users not to be shown content unless they actively click to view – could enhance them.

We had 2,800 adults use a mock-up of a Video Sharing Platform

Each person was randomised into a different groups and shown six video clips in a random order. The videos were a mix of neutral and potentially harmful clips, with an alert message placed ahead of the potentially harmful ones. We varied the alert messages between groups to see the impact.

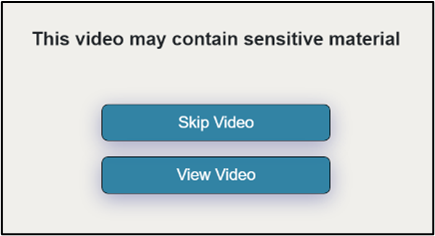

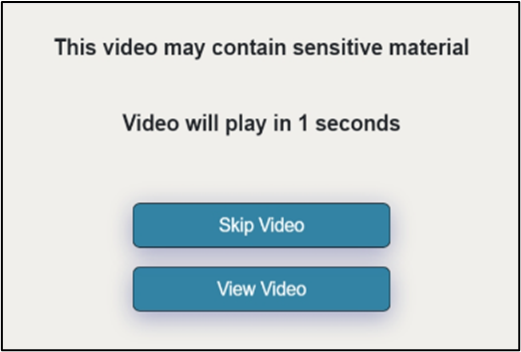

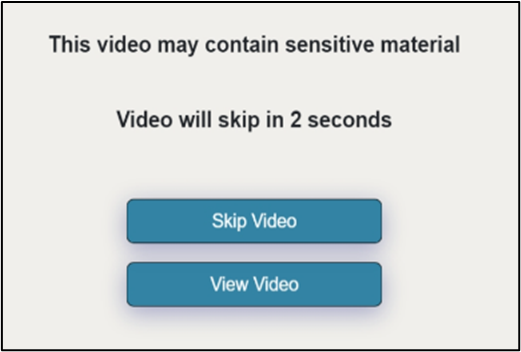

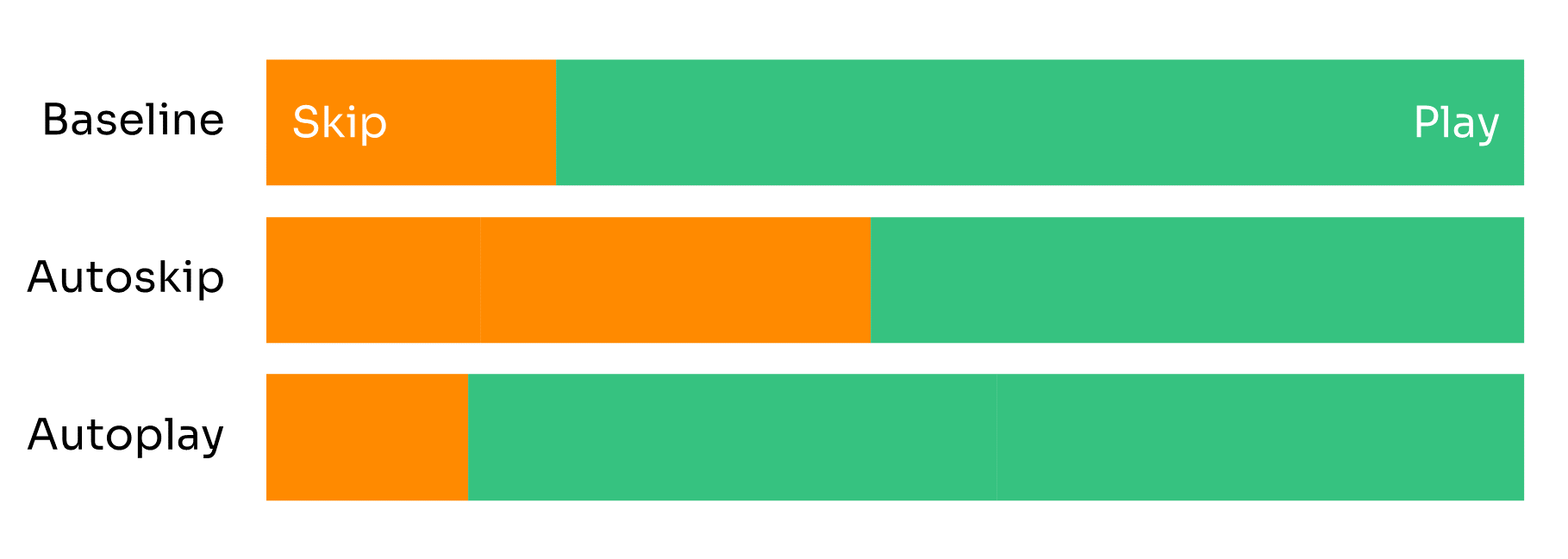

First, we set a baseline to understand how participants would react to a simple alert message (pictured).

Then we added autoskip and autoplay functions. The harmful clips would either automatically skip or automatically play after five seconds of inaction. Participants were able to make their own decision during the five second countdown.

We expected the autoskip alert to reduce viewing, and the autoplay alert to increase it. What we didn’t know was how often participants would let the default kick in instead of making an active choice for each, or what scale of impact we might see.

------------------------------------------------------

In response to the baseline alert message, just under one in four participants skipped the videos. Participants had to click to skip or play the video. This shows us what users choose without the influence of autoplay or autoskip.

When we introduce these features, participant behaviour changes substantially. Autoskip increased the proportion skipping to 48%. Autoplay reduced skipping to only 16%, leading over eight in ten to start watching the clips. The difference in the scale of impact between the two is pronounced. The autoskip amplifies the effect of the alert, but the impact of autoplay is much less strong.

When we introduce these features, participant behaviour changes substantially. Autoskip increased the proportion skipping to 48%. Autoplay reduced skipping to only 16%, leading over eight in ten to start watching the clips. The difference in the scale of impact between the two is pronounced. The autoskip amplifies the effect of the alert, but the impact of autoplay is much less strong.

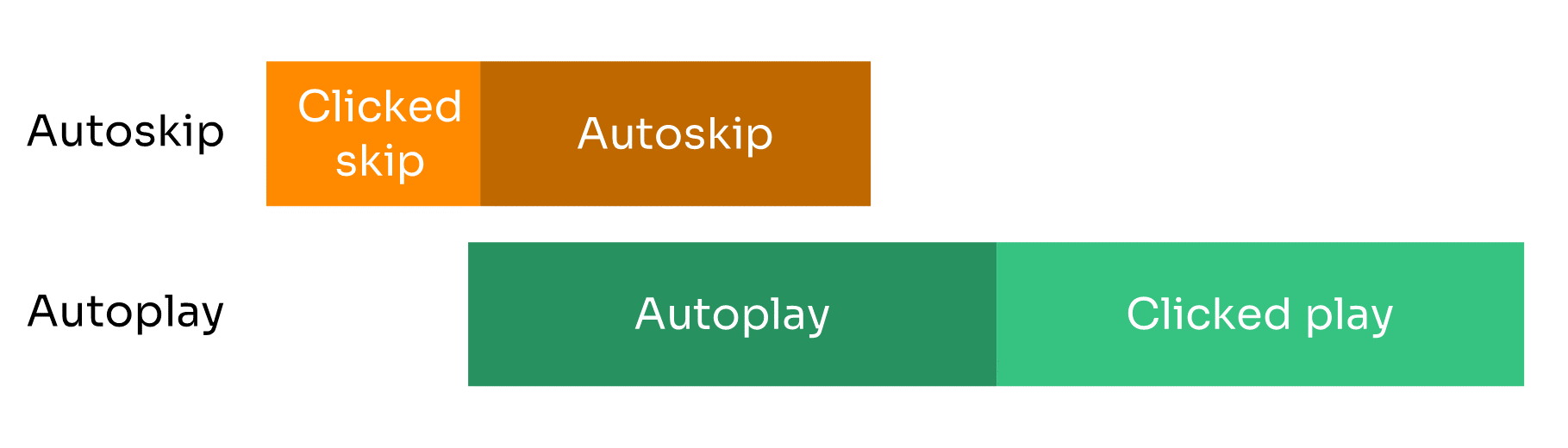

Looking closer, a further difference emerges. Out of those who skipped the videos with an alert with autoskip, around two-thirds allowed the autoskip to kick in, rather than actively clicking ‘skip’ themselves. The majority simply go with the flow.

Looking closer, a further difference emerges. Out of those who skipped the videos with an alert with autoskip, around two-thirds allowed the autoskip to kick in, rather than actively clicking ‘skip’ themselves. The majority simply go with the flow.

Conversely, for those who watched the videos with an alert with autoplay, only half allow the autoplay to kick in, and half actively click to watch.

Conversely, for those who watched the videos with an alert with autoplay, only half allow the autoplay to kick in, and half actively click to watch.

More users go with the flow when presented with an autoskip, but more make active choices with an autoplay alert. The extent to which the automatic choice shapes user behaviour is not uniform. That’s significant and it’s worth exploring.

Reinforcement versus inconsistency

One explanation is that the difference is due to reinforcement vs inconsistency.

The autoskip function reinforces the message of the alert. The default action (to skip) and the purpose of the alert (to warn people of sensitive material) are aligned. Defaults have been shown to be more effective when they act as an endorsement of what the user should do. In this case, the reinforcement of the alert message by the autoskip default may have heightened the impression of endorsement, and increased acceptance of the default and the overall impact of the alert.

In contrast, alerts including autoplay led to a greater proportion of participants going out of their way to override the autoplay and actively choose to watch the content. The combination of an alert and an autoplay function may have jarred with participants. The purpose of an alert is to warn about risk. Perhaps the alert being accompanied by a default option to watch the content caused participants to sit up and take note rather than accept the default.

Easy doesn’t equal memorable

Although not conclusive, we saw signs from the questionnaire at the end of the trial that support this explanation.

We asked participants if they regarded the alerts as recommendations. We would have expected more of those who had seen the autoskip alert to consider it to be a recommendation compared to the autoplay alert. But there were no significant differences between the two groups.

On the other hand, accurate recall of the alert with autoplay was much higher (61%) than for the alert with autoskip (39%). The autoplay feature stood out.

Whilst at first surprising, these findings fit with the concept of cognitive fluency. When faced with undemanding tasks, we tend to experience cognitive fluency. We don’t need to concentrate to carry them out. Tasks that require more mental effort are said to cause cognitive strain. Counter-intuitively, people tend to make correct decisions more frequently when faced with cognitive strain. If it’s too easy, we tend not to engage so thoroughly.

In our experiment, the theory would be that when users encounter the combination of an alert and an autoskip function, they experience cognitive fluency. They do not need to exert cognitive effort to decide what to do. They go with the flow and their action (or lack of it) doesn’t register strongly. Their perception of whether the alert is a recommendation isn’t altered. In contrast, the jarring of the alert and the autoplay function causes cognitive strain, leading to effortful thinking. And that effort improved accurate recall.

What does this mean?

It’s worth recognising the limitations of our methodology – participants were aware they were part of a study and might not have behaved as they would in real life. Nevertheless, we consider this type of evidence to be valuable in building our evidence base on online safety. We discuss the limitations to this methodology in this discussion paper.

Autoplay and autoskip are not neutral design features

When combined with alerts, they cause substantial changes in viewing behaviour compared to static warnings. The evidence from our experiment suggests that design features that automatically direct users without them actively choosing tend to kick in more often when they’re consistent, reinforcing and amplifying the alert message. On the other hand, an automatic step in the user journey that is inconsistent with user expectations appears to jar, causing more users to take notice and make their own choice.

Our study provides valuable evidence on the extent to which safety measures can be influenced by design features such as autoplay. In one sense the results corroborate the concerns around autoplay mentioned at the start of this piece – the scale of influence when the alert and the autoskip are combined is striking, even considering the experimental setting. On the other hand, we do see signs of user vigilance when they are being steered in unexpected directions.

These design features can be used to enhance or undermine the effect of safety measures. Ultimately, It is not the design feature itself that is key, but how it is deployed.

This blog was co-authored by Alex Jenkins, Rupert Gill and Jonathan Porter, with support from John Ivory, based on research conducted with Kantar Public Behavioural Practice.

Disclaimer: The analyses, opinions and findings in this article should not be interpreted as an official position of Ofcom. Ofcom’s Behavioural Insight blogs are written as points of interest and are the personal views of the author(s). They are not intended to be an official statement of Ofcom's policy or thinking.