Earlier this year we published Ofcom’s final decision (PDF, 3.2 MB) in a competition case, which resulted in us fining Sepura £1.5m for breaching competition law. This came after the company exchanged competitively-sensitive information with its competitor Motorola, during a procurement process. In this article, we shine a light on some of the important legal issues the case raises.

What happened in the case?

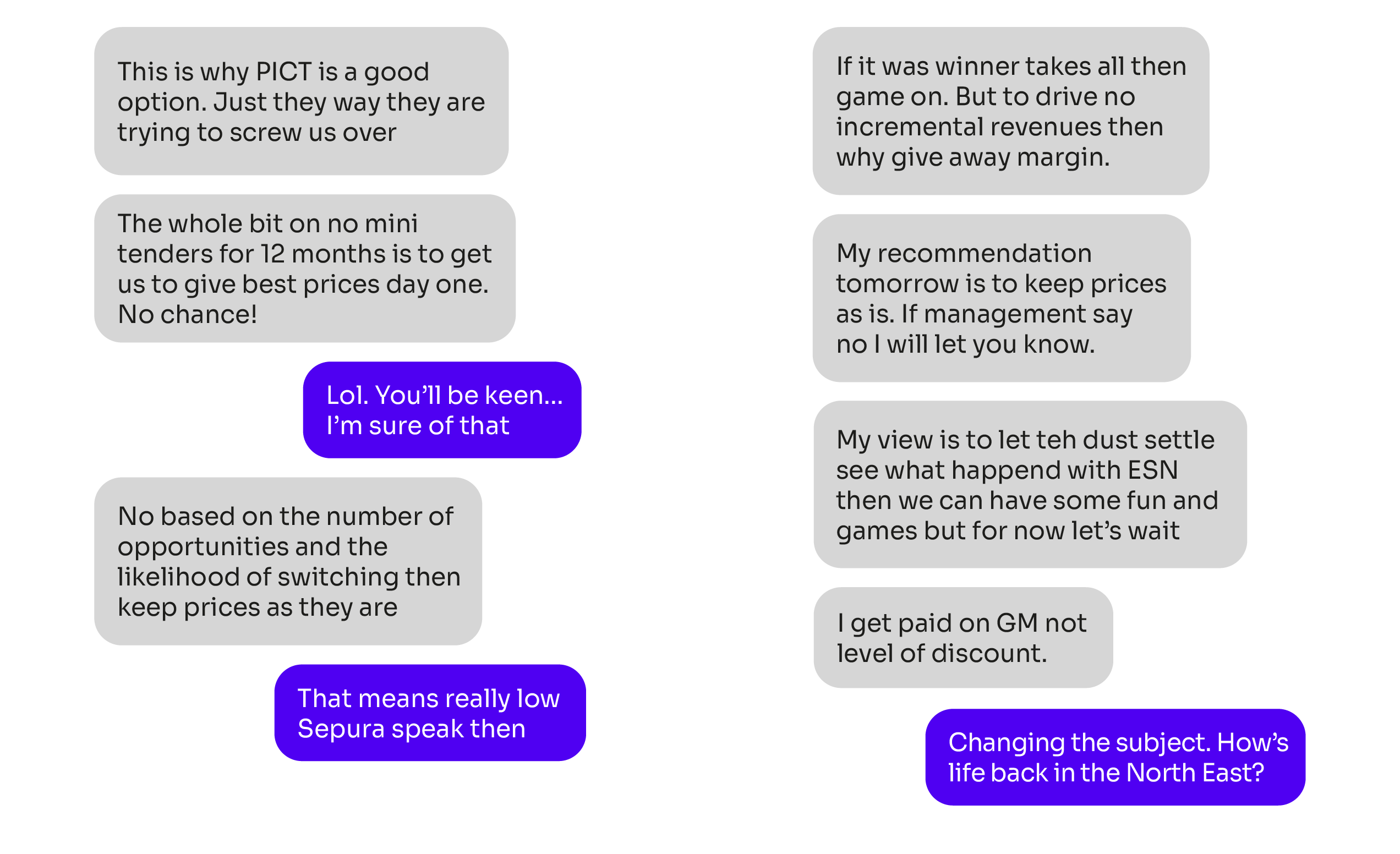

The fine resulted from an exchange of 69 text messages between two senior individuals at Sepura (in grey below) and Motorola (in blue) which included the following messages:

In an exchange of text messages lasting over two hours, the Sepura employee repeatedly disclosed Sepura's pricing intentions in relation to an upcoming tender to a counterpart at Motorola.

Motorola did not object to any of those disclosures, although its employee eventually decided to change the subject after 48 messages were exchanged relating to the tender.

The Motorola employee subsequently reported the exchange internally and Motorola took various steps in an attempt to ring-fence the information and mitigate its impact on Motorola’s bid, but still submitted a bid.

The company later contacted the Competition and Markets Authority to apply for leniency.

A concerted practice

Sepura was fined for participating in a concerted practice, which the Court of Appeal has previously described as ‘a form of co-ordination between undertakings which, without going so far as to amount to an agreement properly so called, knowingly substitutes a practical co-operation between them for the risks of competition’ (Balmoral Tanks v CMA [2019] EWCA Civ 16, paragraph 16).

The case raised some important legal issues around the concept of a concerted practice, including the presumption of a causal connection between an exchange of competitively-sensitive information and participants’ subsequent conduct.

In particular, it was argued in this case that there can be no concerted practice in a one-off exchange of information between two competitors where the only recipient of competitively-sensitive information subsequently takes various internal compliance steps to ring-fence the information and applies for leniency.

The presumption of a causal connection

For an exchange of competitively-sensitive information to breach competition law, a number of legal tests must be satisfied.

One of the tests requires there to be a causal connection between the exchange and participants’ subsequent conduct. There is a legal presumption that a causal connection does exist, reflecting the fact a recipient of competitively-sensitive information is assumed to take that information into account in determining its future conduct. The presumption can however be rebutted.

Examples from case law where the presumption can be rebutted include so called ‘public distancing’ - for example, by clearly communicating to other participants that the recipient does not accept the information and will not take it into account - and reporting to the relevant authorities.

What did Ofcom decide?

Our starting point was that there will be causal connection unless the presumption is separately rebutted in relation to all parties’ subsequent conduct. Applying this principle, we separately assessed what Motorola and Sepura gained from the exchange and whether their subsequent conduct rebutted the presumption applicable to their own conduct.

In Motorola’s case, it received information on Sepura’s pricing strategy which significantly reduced uncertainty in relation to Sepura’s subsequent conduct relating to the bid (see paragraphs 641 – 649 and 692 – 728). There is a presumption Motorola would take into account that information when determining its own pricing decisions in response to the tender - and the decision found that Motorola’s subsequent conduct did not rebut this presumption. This was because:

- Motorola did not publicly distance itself from the exchange in accordance with the requirements of the case-law:

- Changing the subject does not amount to open and unequivocal opposition and does not therefore constitute effective public distancing.

- Motorola did not make Sepura aware of the exchange of messages on 5 September 2018 or inform Sepura or the Sepura employee involved that Motorola had taken steps to seek to mitigate the impact of the exchange on its bid.

- While Motorola did apply for leniency, it did so after it submitted its bid and therefore after the causal connection already had the opportunity to crystallise.

- Motorola did not inform the procuring authority of the information exchange. In this context, the European Commission Notice on tools to fight collusion in public procurement and on guidance on how to apply the related exclusion ground (2021/C 91/01) stresses the importance of reporting any anti-competitive conduct to the procuring authority so that the authority can then decide if it considers the relevant parties have taken appropriate “self-cleansing measures” to ensure their bid is not tainted and remains reliable or whether to exclude either party from the tender process (see section 5.7).

- Motorola’s internal compliance steps were insufficient to rebut the presumption.

Turning to Sepura, the decision found that Motorola’s failure to express any reservations or object to Sepura’s disclosures in relation to Sepura’s pricing strategy reduced uncertainty in relation to Motorola’s subsequent conduct relating to the bid. This is because Sepura would have gained confidence, comfort or assurance from the fact Motorola was aware of Sepura’s pricing intentions and that Motorola would take into account that information in determining Motorola’s own pricing strategy (see paragraphs 650 – 654 and 692 – 728).

There is similarly a presumption that Sepura would take that information into account in determining its own pricing decisions in response to the tender and the decision found that Sepura did nothing to rebut that presumption. The decision also explained that Sepura was at the time unaware of Motorola’s leniency application or any of Motorola’s internal compliance steps which were therefore incapable of rebutting the presumption in relation to Sepura’s subsequent conduct.

What can businesses learn from this case?

There are some key learnings for businesses from this case. Firstly, the importance of businesses implementing effective training and processes to ensure compliance with competition law; and secondly, knowing how to respond in the event of a potential breach.

A failure to do so can have significant consequences including a fine of up to 10% of a company’s annual worldwide turnover, claims for damages and reputational damage. Enforcement action can also be taken against individuals including director disqualification or criminal action which can result in a fine and/or prison.

So as this case shows, it’s vital that parties seeking to distance themselves publicly from an anticompetitive exchange of information by reporting the conduct to the relevant authorities, do so as soon as possible.

Further information is available in the CMA’s Cheating or Competing guide and Short guide on competition law risk.